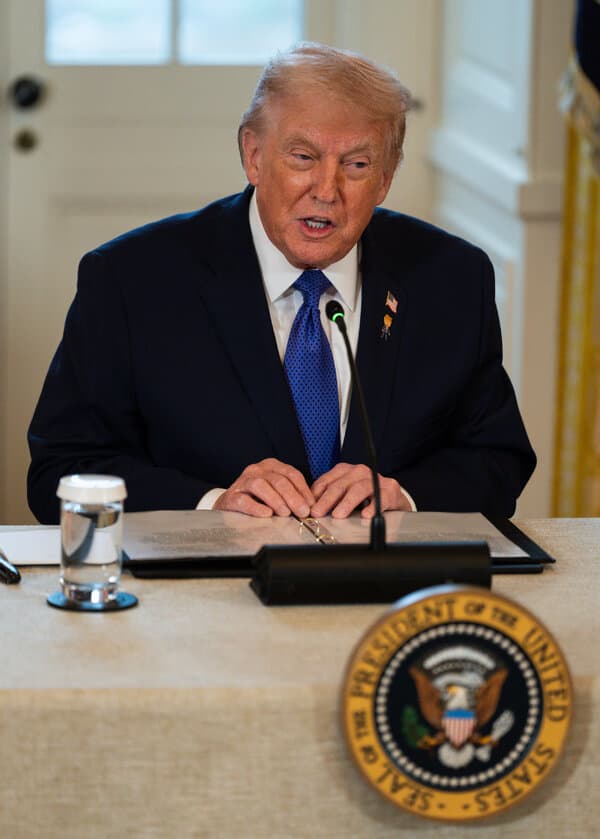

Trump Proposes 10% Credit Card Interest Cap, Reversing on Previous Fee Deregulation

In a significant policy shift, former President Donald Trump has called for a federal cap on credit card interest rates at 10 percent, a move that marks a stark reversal from his previous administration's efforts to dismantle consumer financial protections. The proposal, announced during a campaign rally in Wisconsin, positions the issue as a key part of his economic platform aimed at 'fighting for the American worker' against what he terms 'predatory' banking practices. This proposal puts Trump at odds with the financial industry and complicates the Republican Party's traditional stance on deregulation. During his presidency, Trump signed legislation that rolled back key provisions of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, including provisions that had empowered the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) to oversee and regulate the credit card market more strictly. That legislation, passed in 2018, made it easier for banks to avoid providing certain disclosures and made it more difficult for consumers to collectively sue lenders through class-action lawsuits. Now, Trump is advocating for a policy that would fundamentally alter the business model of major credit card issuers like JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and Citigroup, which rely heavily on interest revenue from revolving balances. At the rally, Trump stated, 'It’s time for Wall Street to pay back to the people. We’re going to cap credit card interest rates at 10 percent. It’s a disgrace what they’re charging.' The proposed cap is significantly lower than current average credit card interest rates, which have hovered around 20 to 22 percent in recent years, according to Federal Reserve data. For subprime borrowers, rates can exceed 29 percent or even 35 percent. Economists immediately raised concerns about the potential unintended consequences of such a strict price control. While the goal is to make borrowing cheaper for consumers carrying balances, a hard cap could lead to a drastic reduction in credit availability. Lenders, facing a ceiling on the potential return they can earn on risky loans, would likely tighten lending standards, denying cards to consumers with lower credit scores or limited credit history. This could force those borrowers toward less regulated and often more predatory lending options, such as payday loans or pawn shops. The proposal also reignites the debate over the role of the CFPB. The agency, which was the brainchild of Senator Elizabeth Warren, was significantly weakened during the Trump administration, with its funding structure challenged and its enforcement powers curtailed. A 10 percent cap would likely require a robust regulator to enforce, presenting a challenge if the administration were to reinstate its previous stance on the agency. The banking industry reacted swiftly and negatively to the proposal. The American Bankers Association released a statement warning that a 10 percent cap 'would make it impossible for banks to issue credit cards to millions of consumers, particularly those who are young, have lower incomes, or are just starting to build their credit history.' They argued that interest rates reflect the cost of borrowing funds, the risk of default, and the cost of fraud and operations, suggesting that a one-size-fits-all cap ignores the risk-based pricing model of the industry. Conversely, consumer advocacy groups, which have long campaigned against high interest rates and fees, expressed cautious optimism. They argue that the credit card market is highly concentrated and that competition does not effectively drive down rates. However, even some advocates noted that a 10 percent cap might be too low to be practical without causing significant credit contraction, suggesting a tiered cap or other regulatory approaches might be more effective. The political timing of the announcement is notable. It comes as the Biden administration has also taken steps to regulate 'junk fees,' including late fees and over-limit charges, though those measures have faced legal challenges from the banking lobby. Trump's proposal goes significantly further by targeting the core revenue stream of credit products. It creates a complex political dynamic, as it appeals to populist sentiment but clashes with the free-market ideology prevalent in the GOP. It also potentially encroaches on the territory of progressive Democrats, creating a rare area of overlap in rhetoric, though the mechanisms proposed to achieve relief differ. If implemented, the economic impact would be profound. Consumer spending, which is heavily fueled by credit, could see shifts. Savings rates might increase as the incentive to carry high-interest debt decreases, or borrowing could move to other sectors. The housing market could see ripple effects if credit card availability tightens and consumer debt-to-income ratios improve or degrade depending on individual circumstances. The proposal sets the stage for a contentious economic debate leading up to the election, pitting the desire for consumer relief against the realities of modern banking and credit risk management. It remains unclear exactly how such a cap would be legislated, whether through a new act of Congress, a directive to the Federal Reserve, or a rule issued by a revived CFPB. The concept of usury laws, which set maximum interest rates, has a long history in the U.S., but federal preemption has often allowed banks to export rates from their home state, effectively bypassing strict state-level caps. A federal cap would require overcoming significant legal and legislative hurdles, including potential challenges based on the Commerce Clause or due process. As the campaign trail heats up, this proposal ensures that the regulation of financial services and the cost of consumer debt will remain front and center in the national conversation.