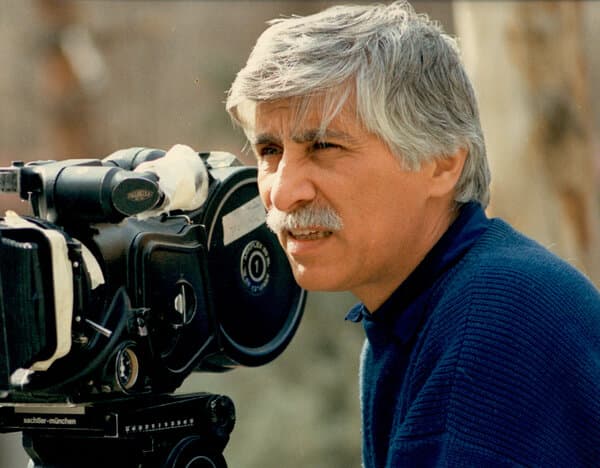

Bahram Beyzaie, Pioneering Leader of Iran's New Wave Cinema, Passes Away at 87

Bahram Beyzaie, a towering figure in Iranian cinema who helped lead the country's New Wave movement, has died at the age of 87. His passing marks the end of an era for Iranian arts and culture, as he was one of the last remaining giants of a generation of filmmakers who revolutionized Persian cinema in the 1960s and 1970s. Beyzaie was not merely a filmmaker; he was a polymath who wore the hats of playwright, screenwriter, academic, and scholar with equal distinction. His death represents a profound loss not only for the Iranian artistic community but for cinema lovers worldwide who appreciated his unique blend of ancient Persian mythology, modern existential philosophy, and humanistic storytelling. Born in 1938 in Tehran, Beyzaie came of age during a period of intense cultural fermentation in Iran. He began his career in the late 1950s, initially working in theater and writing critical essays on the dramatic arts. His early interests were deeply rooted in the rich tapestry of Iranian history and pre-Islamic traditions. Unlike many of his contemporaries who looked to the West for inspiration, Beyzaie turned inward, seeking to revive the ancient storytelling traditions of his homeland. He was deeply influenced by Persian mythological narratives, Zoroastrian symbolism, and the ritualistic theater of the Ta'zieh, a form of Shia passion play. This scholarly foundation would become the bedrock of his cinematic oeuvre. The Iranian New Wave (Moj-e No) was a significant film movement that emerged in the late 1960s, characterized by its artistic ambition, social critique, and poetic realism. While Dariush Mehrjui’s 'The Cow' (1969) is often cited as the film that formally launched the movement, Beyzaie was a vital intellectual and creative force within it. His first feature film, 'Bashu, the Little Stranger' (1986), though released later, encapsulated the spirit of the New Wave. Shot during the tumultuous years of the Iran-Iraq War, the film offered a poignant anti-war message. It told the story of a young boy from the south who flees the bombing of his village and finds refuge in the northern forests of Iran, taken in by a rural woman. 'Bashu' was revolutionary not just for its thematic boldness—addressing the ethnic and cultural divides within Iran—but for its visual poetry and lack of melodramatic sentimentality. It subtly criticized the absurdity of war while championing human compassion and unity above tribal and nationalistic divisions. The film was initially banned by Iranian authorities for its sensitive themes but was later released to critical acclaim, eventually being voted the best Iranian film of all time in a 1999 poll by Iranian critics. This single work cemented Beyzaie’s reputation as a filmmaker capable of navigating the complex political and cultural landscape of post-revolutionary Iran while maintaining his artistic integrity. However, Beyzaie’s journey was not without significant hurdles. Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, like many intellectuals and artists, he faced censorship and restrictions. His work was often scrutinized for its philosophical depth and perceived critiques of societal norms. He eventually left Iran, teaching at universities in the United States and continuing his artistic endeavors in exile. This exile, while painful, allowed him to maintain a global perspective and continue writing and teaching, influencing a new generation of filmmakers and scholars who looked up to him as a mentor and a beacon of artistic freedom. Beyond 'Bashu', Beyzaie’s filmography includes works such as 'Kalāgh' (The Crow, 1987) and 'Mār' (The Snake, 1990). 'The Crow' is perhaps his most experimental and challenging film, a meta-narrative about a filmmaker attempting to make a movie about the execution of a political prisoner. It is a stark, black-and-white meditation on the nature of art, resistance, and the oppressive machinery of the state. The film’s complex structure and bleak tone made it difficult for many viewers, but it is regarded by critics as a masterpiece of the Iranian New Wave’s intellectual rigor. Beyzaie often used allegory and metaphor to express sentiments that could not be stated directly, a hallmark of intelligent Iranian cinema during restrictive periods. As a playwright, Beyzaie was equally prolific. He wrote over fifty plays, many of which were performed in Iran and abroad. He sought to create a 'third theater'—one that was neither wholly Western nor strictly traditional, but a synthesis of the two. He experimented with form, incorporating puppets, masks, and ritualistic movements into his stage works. His scholarly writings on theater, particularly his analysis of the Ta'zieh and the Siah-Bazi (a form of traditional comic performance), remain important texts in the study of Persian performing arts. He argued that true Iranian art must be rooted in its own cultural soil rather than being a mere copy of European or American trends. Beyzaie’s influence on contemporary Iranian cinema is immeasurable. Directors like Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, and Jafar Panahi, while having their own distinct styles, all owe a debt to the path Beyzaie and his peers blazed. He showed that it was possible to make deeply personal, artistically sophisticated films within the constraints of the Iranian system. He pioneered a cinematic language that was poetic, symbolic, and deeply humanistic. His focus on marginalized figures—children, ethnic minorities, women, the rural poor—gave a voice to those often ignored by mainstream cinema. In recent years, the international film community has paid increasing tribute to his legacy. Retrospectives of his work have been held at major festivals, including the Cannes Film Festival, where he was honored in 2020. Critics note that his films have a timeless quality; the themes of displacement, identity, the clash between tradition and modernity, and the search for human connection are as relevant today as they were decades ago. The news of his death has elicited an outpouring of grief from artists and intellectuals across the globe. Tributes have poured in describing him as a 'master storyteller,' a 'defiant intellectual,' and the 'conscience of Iranian cinema.' His son, Baran Beyzaie, also a filmmaker, confirmed his passing, noting that his father had been in declining health for some time. Despite the physical distance from his homeland, Beyzaie remained spiritually connected to Iran, often expressing a deep longing for the landscapes and cultures that inspired his life's work. Bahram Beyzaie’s legacy is twofold. First, he created a body of work that stands as a testament to the power of art to transcend boundaries and speak to universal human experiences. Second, he served as a bridge between the ancient and the modern, reminding the world of Iran’s profound cultural heritage. He will be remembered not just as a leader of the New Wave, but as a philosopher-filmmaker who used the camera as a tool to explore the deepest questions of existence. His death leaves a void that will be hard to fill, but his films will continue to educate, inspire, and challenge audiences for generations to come. The Iranian New Wave was a brief, brilliant flash in the history of cinema, and Bahram Beyzaie was one of its brightest stars.